The HTTP specifications explain HTTP messages fairly well, but they don’t talk much about HTTP connections, the critical plumbing that HTTP messages flow through. If you’re a programmer writing HTTP applications, you need to under- stand the ins and outs of HTTP connections and how to use them.

HTTP connection management has been a bit of a black art, learned as much from experimentation and apprenticeship as from published literature. In this chapter, you’ll learn about:

•

How HTTP uses TCP connections

•

Delays, bottlenecks and clogs in TCP connections

•

HTTP optimizations, including parallel, keep-alive, and pipelined connections

•

Dos and don’ts for managing connections

1. TCP Connections

Just about all of world's HTTP communication is carried over TCP/IP, a popular layered set of packet-switched network protocol spoken by computers and network devices around the globe. A client application can open a TCP/IP connection to a server application, running just about anywhere in the world. Once the connection is established, messages exchanged between the client’s and server’s computers will never be lost, damaged, or received out of order.

Say you want the latest power tools price list from Joe’s Hardware store:

http://www.joes-hardware.com:80/power-tools.html

When given this URL, your browser performs the steps shown in Figure 4-1. In Steps 1–3, the IP address and port number of the server are pulled from the URL. A TCP connection is made to the web server in Step 4, and a request message is sent across the connection in Step 5. The response is read in Step 6, and the connection is closed in Step 7.

Figure 4-1. Web browsers talk to web servers over TCP connections

1.1. TCP Reliable Data Pipes

HTTP connections really are nothing more than TCP connections, plus a few rules about how to use them. TCP connections are the reliable connections of the Inter-net. To send data accurately and quickly, you need to know the basics of TCP.

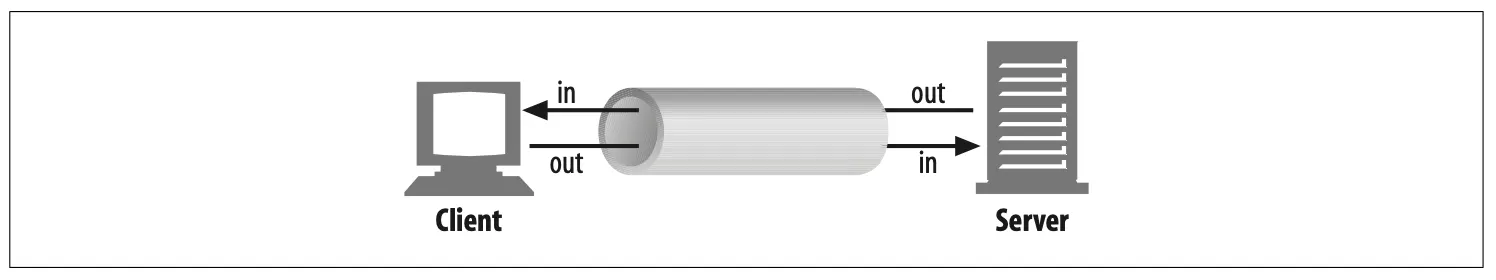

TCP gives HTTP a reliable bit pipe. Bytes stuffed in one side of a TCP connection come out the other side correctly, and in the right order (see Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. TCP carries HTTP data in order, and without corruption

1.2. TCP Streams Are Segmented and Shipped by IP Packets

TCP sends its data in little chunks called IP packets (or IP datagrams). In this way, HTTP is the top layer in a “protocol stack” of “HTTP over TCP over IP,” as depicted in Figure 4-3a. A secure variant, HTTPS, inserts a cryptographic encryption layer (called TLS or SSL) between HTTP and TCP (Figure 4-3b).

Figure 4-3. HTTP and HTTPS network protocol stacks

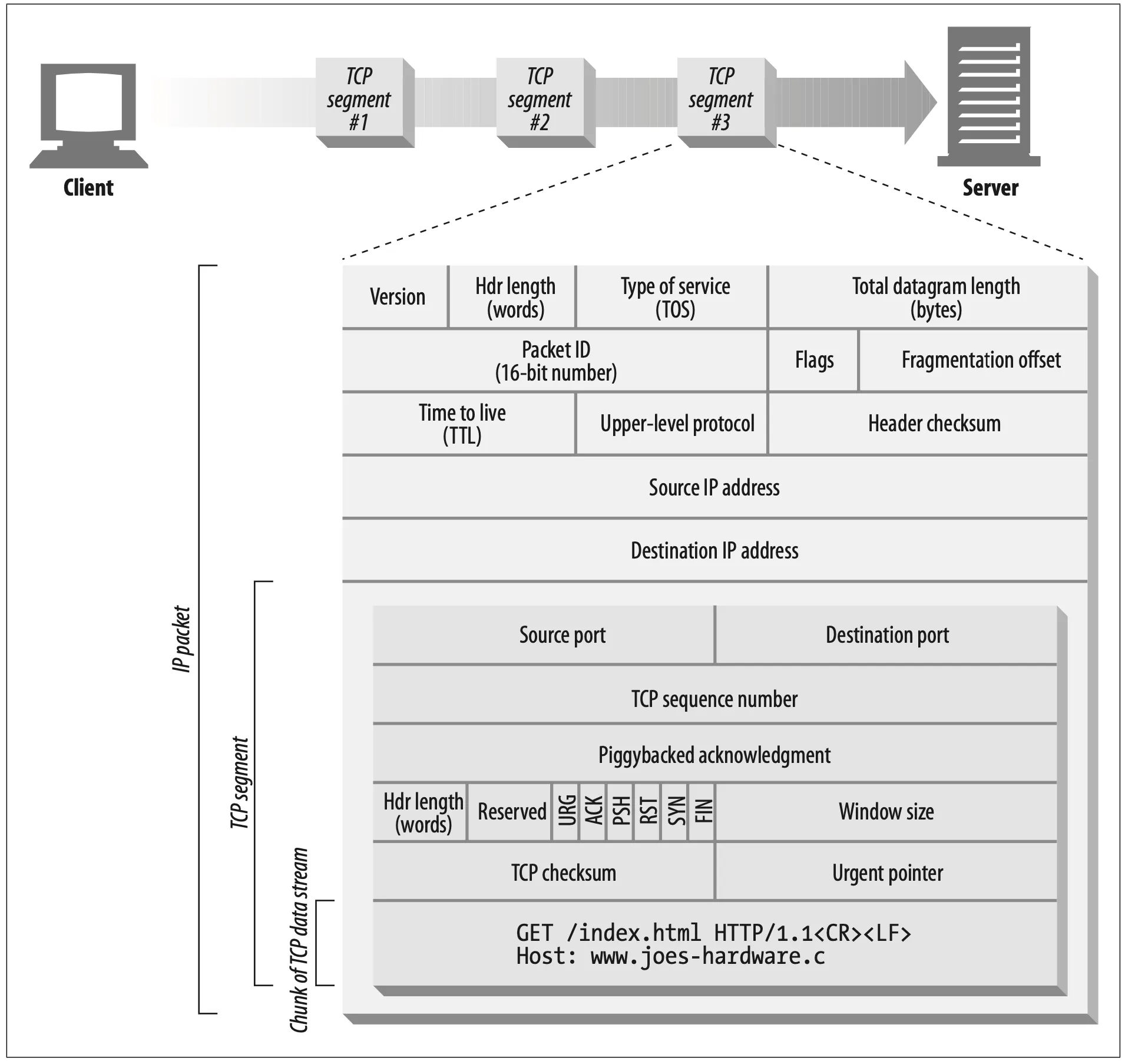

When HTTP wants to transmit a message, it streams the contents of the message data, in order, through an open TCP connection. TCP takes the stream of data, chops up the data stream into chunks called segments, and transports the segments across the Internet inside envelopes called IP packets (see Figure 4-4). This is all han- dled by the TCP/IP software; the HTTP programmer sees none of it.

Figure 4-4. IP packets carry TCP segments, which carry chunks of the TCP data stream.

Each TCP segment is carried by an IP packet from one IP address to another IP

address. Each of these IP packets contains:

•

An IP packet header (usually 20 bytes)

•

A TCP segment header (usually 20 bytes)

•

A chunk of TCP data (0 or more bytes)

The IP header contains the source and destination IP addresses, the size, and other flags. The TCP segment header contains TCP port numbers, TCP control flags, and numeric values used for data ordering and integrity checking.

1.3. Keeping TCP Connections Straight

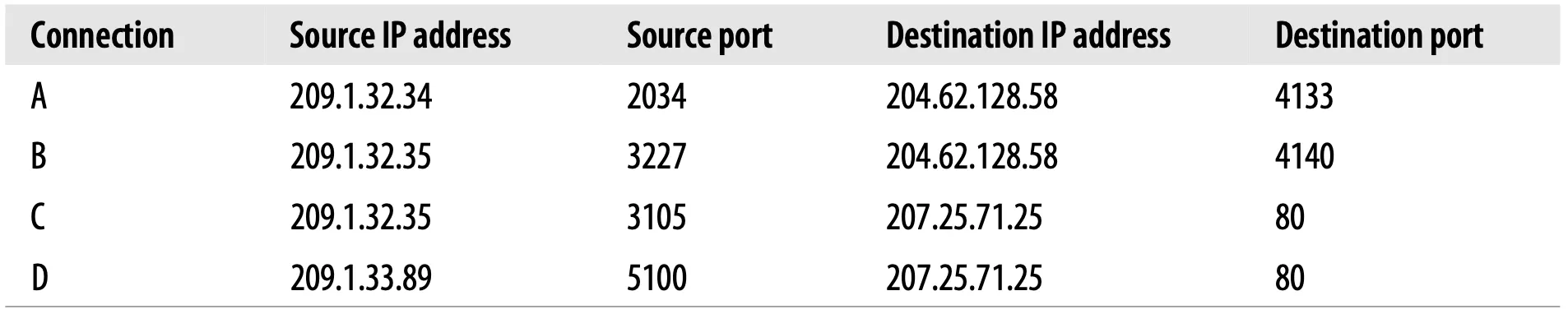

A computer might have several TCP connections open at any one time. TCP keeps all these connections straight through port numbers.

Port numbers are like employees’ phone extensions. Just as a company’s main phone number gets you to the front desk and the extension gets you to the right employee, the IP address gets you to the right computer and the port number gets you to the right application. A TCP connection is distinguished by four values:

<source-IP-address, source-port, destination-IP-address, destination-port>

Together, these four values uniquely define a connection. Two different TCP connections are not allowed to have the same values for all four address components (but different connections can have the same values for some of the components).

In Figure 4-5, there are four connections: A, B, C and D. The relevant information for each port is listed in Table 4-1.

Table 4-1. TCP connection values

Figure 4-5. Four distinct TCP connections

Note that some of the connections share the same destination port number (C and D both have destination port 80). Some of the connections have the same source IP address (B and C). Some have the same destination IP address (A and B, and C and D). But no two different connections share all four identical values.

1.4. Programming with TCP Sockets

Operating systems provide different facilities for manipulating their TCP connec- tions. Let’s take a quick look at one TCP programming interface, to make things concrete.Table4-2showssomeoftheprimaryinterfacesprovidedbythesockets API. This sockets API hides all the details of TCP and IP from the HTTP program- mer. The sockets API was first developed for the Unix operating system, but variants are now available for almost every operating system and language.

Table 4-2. Common socket interface functions for programming TCP connections

The sockets API lets you create TCP endpoint data structures, connect these end- points to remote server TCP endpoints, and read and write data streams. The TCP API hides all the details of the underlying network protocol handshaking and the segmentation and reassembly of the TCP data stream to and from IP packets.

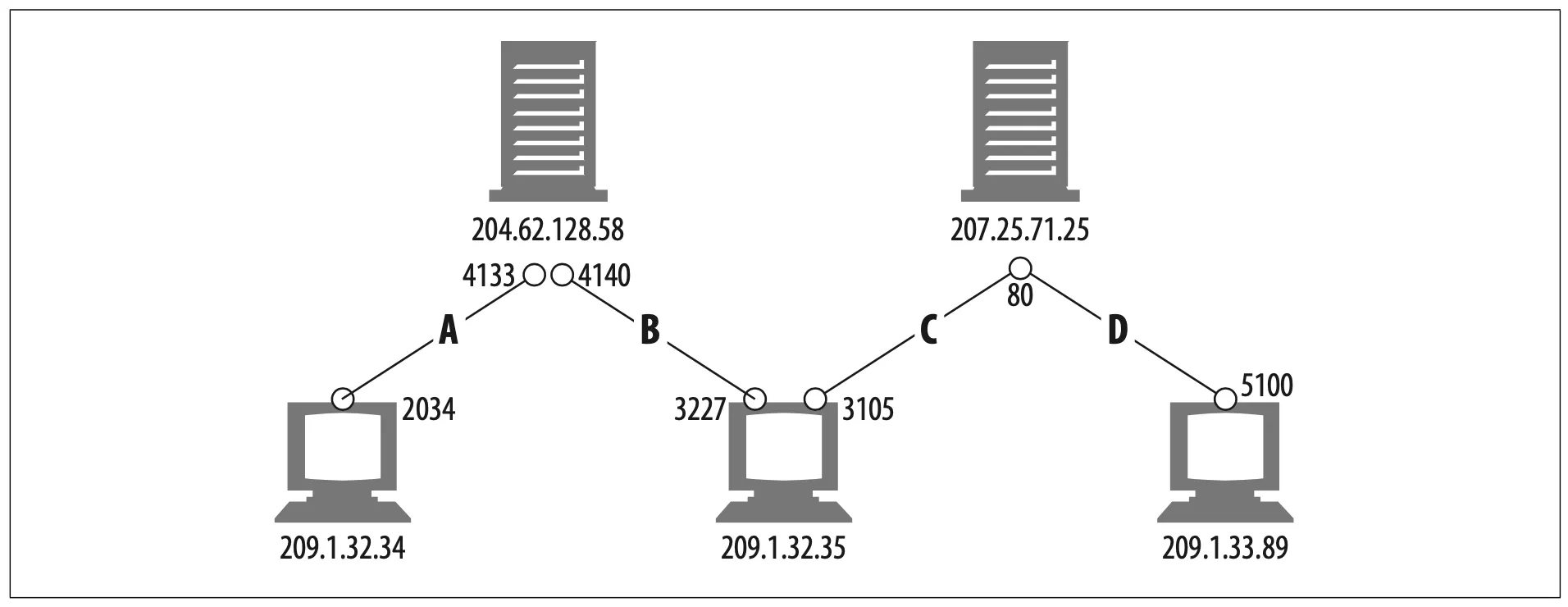

In Figure 4-1, we showed how a web browser could download the power-tools.html web page from Joe’s Hardware store using HTTP. The pseudocode in Figure 4-6 sketches how we might use the sockets API to highlight the steps the client and server could perform to implement this HTTP transaction.

Figure 4-6. How TCP clients and servers communicate using the TCP sockets interface

We begin with the web server waiting for a connection (Figure 4-6, S4). The client determines the IP address and port number from the URL and proceeds to establish a TCP connection to the server (Figure 4-6, C3). Establishing a connection can take a while, depending on how far away the server is, the load on the server, and the congestion of the Internet.

Once the connection is set up, the client sends the HTTP request (Figure 4-6, C5) and the server reads it (Figure 4-6, S6). Once the server gets the entire request mes- sage, it processes the request, performs the requested action (Figure 4-6, S7), and writes the data back to the client. The client reads it (Figure 4-6, C6) and processes the response data (Figure 4-6, C7).

2. TCP Performance Considerations

Because HTTP is layered directly on TCP, the performance of HTTP transactions depends critically on the performance of the underlying TCP plumbing. This section highlights some significant performance considerations of these TCP connections. By understanding some of the basic performance characteristics of TCP, you’ll better appreciate HTTP’s connection optimization features, and you’ll be able to design and implement higher-performance HTTP applications.

2.1. HTTP Transaction Delays

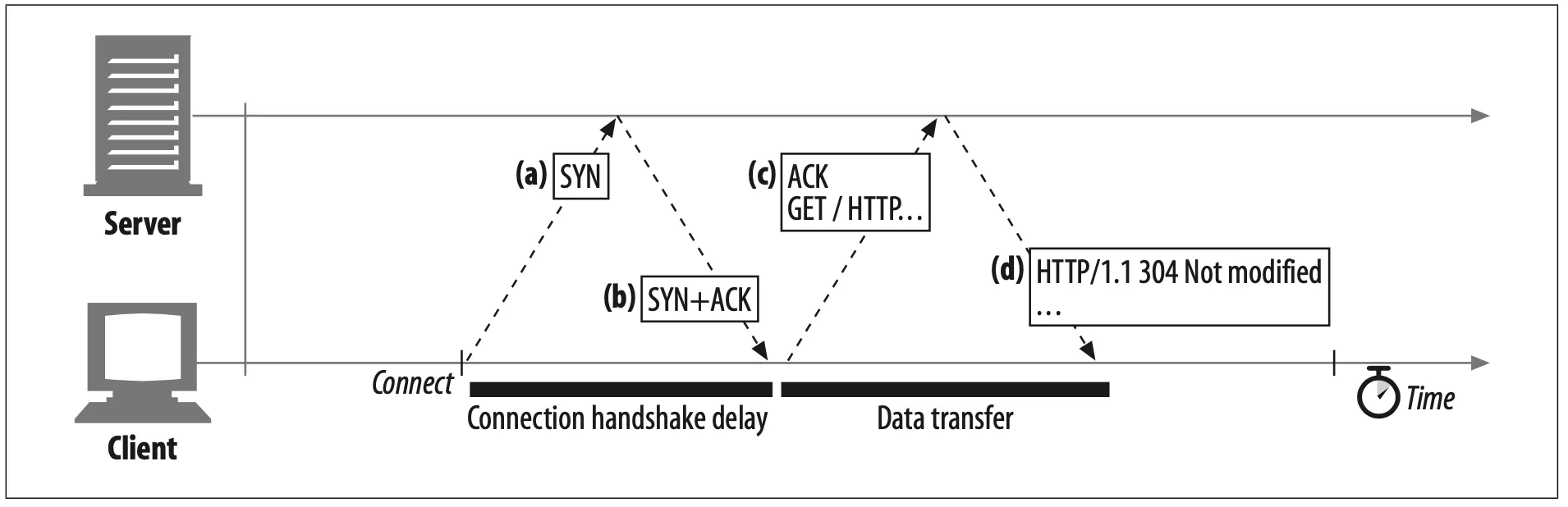

Let’s start our TCP performance tour by reviewing what networking delays occur in the course of an HTTP request. Figure 4-7 depicts the major connect, transfer, and processing delays for an HTTP transaction.

Timeline of a serial HTTP transaction

Notice that the transaction processing time can be quite small compared to the time required to set up TCP connections and transfer the request and response messages. Unless the client or server is overloaded or executing complex dynamic resources, most HTTP delays are caused by TCP network delays.

There are several possible causes of delay in an HTTP transaction:

1.

A client first needs to determine the IP address and port number of the web server from the URI. If the hostname in the URI was not recently visited, it may take tens of seconds to convert the hostname from a URI into an IP address using the DNS resolution infrastructure.

2.

Next, the client sends a TCP connection request to the server and waits for the server to send back a connection acceptance reply. Connection setup delay occurs for every new TCP connection. This usually takes at most a second or two, but it can add up quickly when hundreds of HTTP transactions are made.

3.

Once the connection is established, the client sends the HTTP request over the newly established TCP pipe. The web server reads the request message from the TCP connection as the data arrives and processes the request. It takes time for the request message to travel over the Internet and get processed by the server.

4.

The web server then writes back the HTTP response, which also takes time.

The magnitude of these TCP network delays depends on hardware speed, the load of the network and server, the size of the request and response messages, and the distance between client and server. The delays also are significantly affected by technical intricacies of the TCP protocol.

2.2. Performance Focus Areas

The remainder of this section outlines some of the most common TCP-related delays affecting HTTP programmers, including the causes and performance impacts of:

•

The TCP connection setup handshake

•

TCP slow-start congestion control

•

Nagle's algorithm for data aggregation

•

TCP's delayed acknowledgment algorithm for piggybacked acknowledgements

•

TIME_WAIT delays and port exhaustion

If you are writing high-performance HTTP software, you should understand each of these factors. If you don't need this level of performance optimization, feel free to skip ahead.

2.3. TCP Connection Handshake Delays

When you set up a new TCP connection, even before you send any data, the TCP software exchanges a series of IP packets to negotiate the terms of the connection (see Figure 4-8). These exchanges can significantly degrade HTTP performance if the connections are used for small data transfers.

Figure 4-8. TCP requires two packet transfers to set up the connection before it can send data

Here are the steps in the TCP connection handshake:

1.

To request a new TCP connection, the client sends a small TCP packet (usually 40-60 bytes) to the server. The packet has a special "SYN" flag set, which means it's a connection request. This is shown in Figure 4-8a.

2.

If the server accepts the connection, it computes some connection parameters and sends a TCP packet back to the client, with both the "SYN" and "ACK" flags set, indicating that the connection request is accepted (see Figure 4-8b).

3.

Finally, the client sends an acknowledgment back to the server, letting it know that the connection was established successfully (see Figure 4-8c). Modern TCP stacks let the client send data in this acknowledgment packet.

The HTTP programmer never sees these packets—they are managed invisibly by the TCP/IP software. All the HTTP programmer sees is a delay when creating a new TCP connection.

The SYN/SYN+ACK handshake (Figure 4-8a and b) creates a measurable delay when HTTP transactions do not exchange much data, as is commonly the case. The TCP connect ACK packet (Figure 4-8c) often is large enough to carry the entire HTTP request message,* and many HTTP server response messages fit into a single IP packet (e.g., when the response is a small HTML file of a decorative graphic, or a 304 Not Modified response to a browser cache request).

The end result is that small HTTP transactions may spend 50% or more of their time doing TCP setup. Later sections will discuss how HTTP allows reuse of existing connections to eliminate the impact of this TCP setup delay.

2.4. Delayed Acknowledgments

Because the Internet itself does not guarantee reliable packet delivery (Internet routers are free to destroy packets at will if they are overloaded), TCP implements its own acknowledgment scheme to guarantee successful data delivery.

Each TCP segment gets a sequence number and a data-integrity checksum. The receiver of each segment returns small acknowledgment packets back to the sender when segments have been received intact. If a sender does not receive an acknowledgment within a specified window of time, the sender concludes the packet was destroyed or corrupted and resends the data.

Because acknowledgments are small, TCP allows them to “piggyback” on outgoing data packets heading in the same direction. By combining returning acknowledgments with outgoing data packets, TCP can make more efficient use of the network. To increase the chances that an acknowledgment will find a data packet headed in the same direction, many TCP stacks implement a “delayed acknowledgment” algo- rithm. Delayed acknowledgments hold outgoing acknowledgments in a buffer for a certain window of time (usually 100–200 milliseconds), looking for an outgoing data packet on which to piggyback. If no outgoing data packet arrives in that time, the acknowledgment is sent in its own packet.

Unfortunately, the bimodal request-reply behavior of HTTP reduces the chances that piggybacking can occur. There just aren’t many packets heading in the reverse direction when you want them. Frequently, the disabled acknowledgment algorithms introduce significant delays. Depending on your operating system, you may be able to adjust or disable the delayed acknowledgment algorithm.

Before you modify any parameters of your TCP stack, be sure you know what you are doing. Algorithms inside TCP were introduced to protect the Internet from poorly designed applications. If you modify any TCP configurations, be absolutely sure your application will not create the problems the algorithms were designed to avoid.

2.5. TCP Slow Start

The performance of TCP data transfer also depends on the age of the TCP connection. TCP connections “tune” themselves over time, initially limiting the maximum speed of the connection and increasing the speed over time as data is transmitted successfully. This tuning is called TCP slow start, and it is used to prevent sudden overloading and congestion of the Internet.

TCP slow start throttles the number of packets a TCP endpoint can have in flight at any one time. Put simply, each time a packet is received successfully, the sender gets permission to send two more packets. If an HTTP transaction has a large amount of data to send, it cannot send all the packets at once. It must send one packet and wait for an acknowledgment; then it can send two packets, each of which must be acknowledged, which allows four packets, etc. This is called “opening the congestion window.”

Because of this congestion-control feature, new connections are slower than “tuned” connections that already have exchanged a modest amount of data. Because tuned connections are faster, HTTP includes facilities that let you reuse existing connections. We’ll talk about these HTTP “persistent connections” later in this chapter.

2.6. Nagle's Algorithm and TCP_NODELAY

TCP has a data stream interface that permits applications to stream data of any size to the TCP stack—even a single byte at a time! But because each TCP segment carries at least 40 bytes of flags and headers, network performance can be degraded severely if TCP sends large numbers of packets containing small amounts of data.

Nagle’s algorithm (named for its creator, John Nagle) attempts to bundle up a large amount of TCP data before sending a packet, aiding network efficiency. The algorithm is described in RFC 896, “Congestion Control in IP/TCP Internetworks.

Nagle’s algorithm discourages the sending of segments that are not full-size (a maximum-size packet is around 1,500 bytes on a LAN, or a few hundred bytes across the Internet). Nagle’s algorithm lets you send a non-full-size packet only if all other packets have been acknowledged. If other packets are still in flight, the partial data is buffered. This buffered data is sent only when pending packets are acknowledged or when the buffer has accumulated enough data to send a full packet.

Nagle’s algorithm causes several HTTP performance problems. First, small HTTP messages may not fill a packet, so they may be delayed waiting for additional data that will never arrive. Second, Nagle’s algorithm interacts poorly with disabled acknowledgments—Nagle’s algorithm will hold up the sending of data until an acknowledgment arrives, but the acknowledgment itself will be delayed 100–200 milliseconds by the delayed acknowledgment algorithm.

HTTP applications often disable Nagle’s algorithm to improve performance, by setting the TCP_NODELAY parameter on their stacks. If you do this, you must ensure that you write large chunks of data to TCP so you don’t create a flurry of small packets.

2.7. TIME_WAIT Accumulation and Port Exhaustion

TIME_WAIT port exhaustion is a serious performance problem that affects perfor- mance benchmarking but is relatively uncommon in real deployments. It warrants special attention because most people involved in performance benchmarking eventually run into this problem and get unexpectedly poor performance.

When a TCP endpoint closes a TCP connection, it maintains in memory a small control block recording the IP addresses and port numbers of the recently closed connection. This information is maintained for a short time, typically around twice the estimated maximum segment lifetime (called “2MSL”; often two minutes*), to make sure a new TCP connection with the same addresses and port numbers is not created during this time. This prevents any stray duplicate packets from the previous connection from accidentally being injected into a new connection that has the same addresses and port numbers. In practice, this algorithm prevents two connections with the exact same IP addresses and port numbers from being created, closed, and recreated within two minutes.

Today’s higher-speed routers make it extremely unlikely that a duplicate packet will show up on a server’s doorstep minutes after a connection closes. Some operating systems set 2MSL to a smaller value, but be careful about overriding this value. Packets do get duplicated, and TCP data will be corrupted if a duplicate packet from a past connection gets inserted into a new stream with the same connection values.

The 2MSL connection close delay normally is not a problem, but in benchmarking situations, it can be. It’s common that only one or a few test load-generation com- puters are connecting to a system under benchmark test, which limits the number of client IP addresses that connect to the server. Furthermore, the server typically is listening on HTTP’s default TCP port, 80. These circumstances limit the availab-le combinations of connection values, at a time when port numbers are blocked from reuse by TIME_WAIT.

In a pathological situation with one client and one web server, of the four values that make up a TCP connection:

<source-IP-address, source-port, detination-IP-address, destination-port>

three of them are fixed—only the source port is free to change:

<client-IP, source-port, server-IP, 80>

Each time the client connects to the server, it gets a new source port in order to have a unique connection. But because a limited number of source ports are available (say, 60,000) and no connection can be reused for 2MSL seconds (say, 120 sec- onds), this limits the connect rate to 60,000 / 120 = 500 transactions/sec. If you keep making optimizations, and your server doesn’t get faster than about 500 transactions/sec, make sure you are not experiencing TIME_WAIT port exhaustion. You can fix this problem by using more client load-generator machines or making sure the client and server rotate through several virtual IP addresses to add more connection combinations.

Even if you do not suffer port exhaustion problems, be careful about having large numbers of open connections or large numbers of control blocks allocated for connection in wait states. Some operating systems slow down dramatically when there are numerous open connections or control blocks.

3. HTTP Connection Handling

The first two sections of this chapter provided a fire-hose tour of TCP connections and their performance implications. If you’d like to learn more about TCP network- ing, check out the resources listed at the end of the chapter.

We’re going to switch gears now and get squarely back to HTTP. The rest of this chapter explains the HTTP technology for manipulating and optimizing connec- tions. We’ll start with the HTTP Connection header, an often misunderstood but important part of HTTP connection management. Then we’ll talk about HTTP’s connection optimization techniques.

3.1. The Oft-Misunderstood Connection Header

HTTP allows a chain of HTTP intermediaries between the client and the ultimate origin server (proxies, caches, etc.). HTTP messages are forwarded hop by hop from the client, through intermediary devices, to the origin server (or the reverse).

In some cases, two adjacent HTTP applications may want to apply a set of options to their shared connection. The HTTP Connection header field has a comma-separated list of connection tokens that specify options for the connection that aren't propagated to other connections. For example, a connection that must be closed after sending the next message can be indicated by Connection: close.

The Connection header sometimes is confusing, because it can carry three different types of tokens:

•

HTTP header field names, listing headers relevant for only this connection

•

Arbitrary token values, describing nonstandard options for this connection

•

The value close, indicating the persistent connection will be closed when done

If a connection token contains the name of an HTTP header field, that header field contains connection-specific information and must not be forwarded. Any header fields listed in the Connection header must be deleted before the message is for- warded. Placing a hop-by-hop header name in a Connection header is known as “protecting the header,” because the Connection header protects against accidental forwarding of the local header. An example is shown in Figure 4-9.

Figure 4-9. The Connection header allows the sender to specify connection-specific options

When an HTTP application receives a message with a Connection header, the receiver parses and applies all options requested by the sender. It then deletes the Connection header and all headers listed in the Connection header before forwarding the message to the next hop. In addition, there are a few hop-by-hop headers that might not be listed as values of a Connection header, but must not be proxied. These include Proxy-Authenticate, Proxy-Connection, Transfer-Encoding, and Upgrade. For more about the Connection header, see Appendix C.

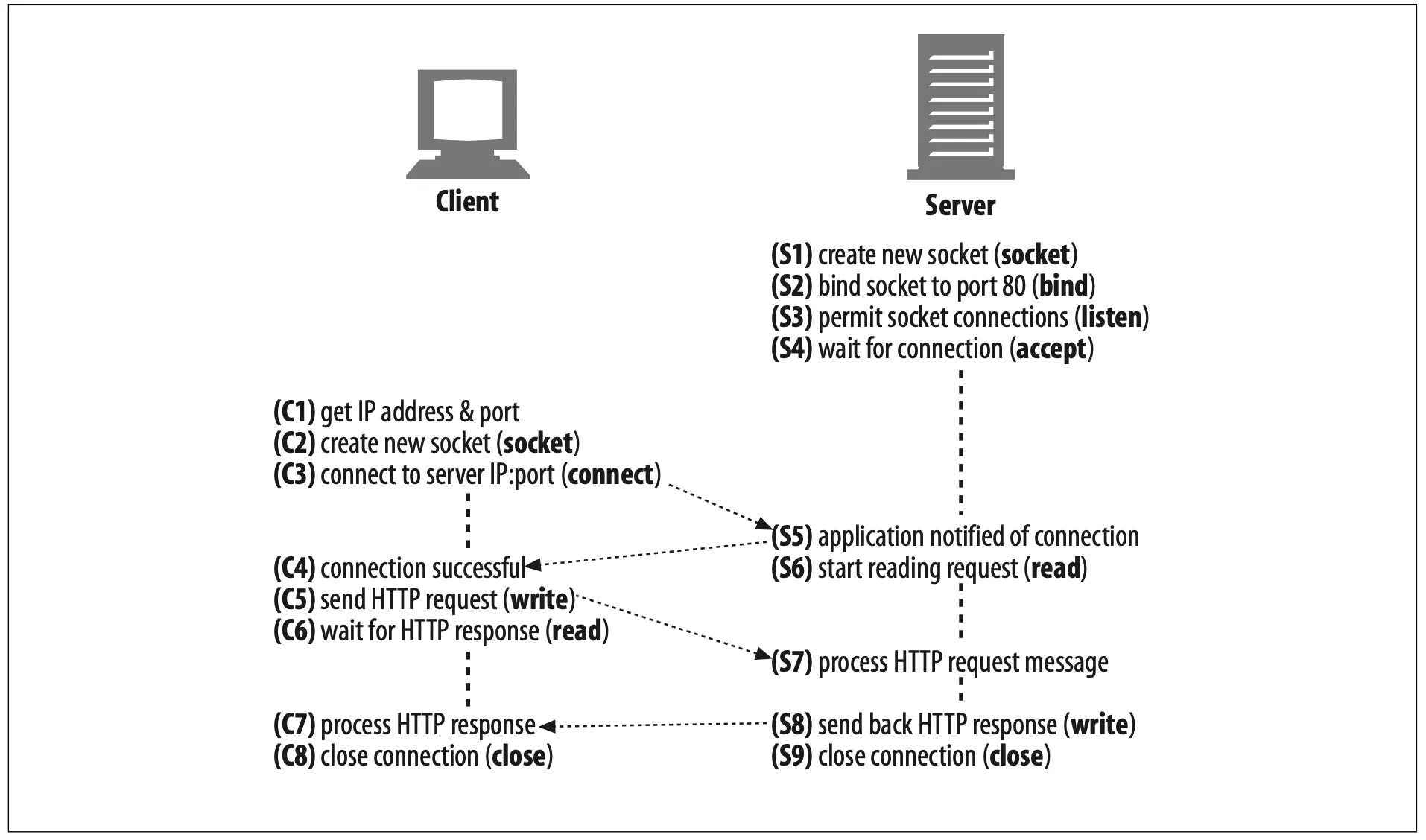

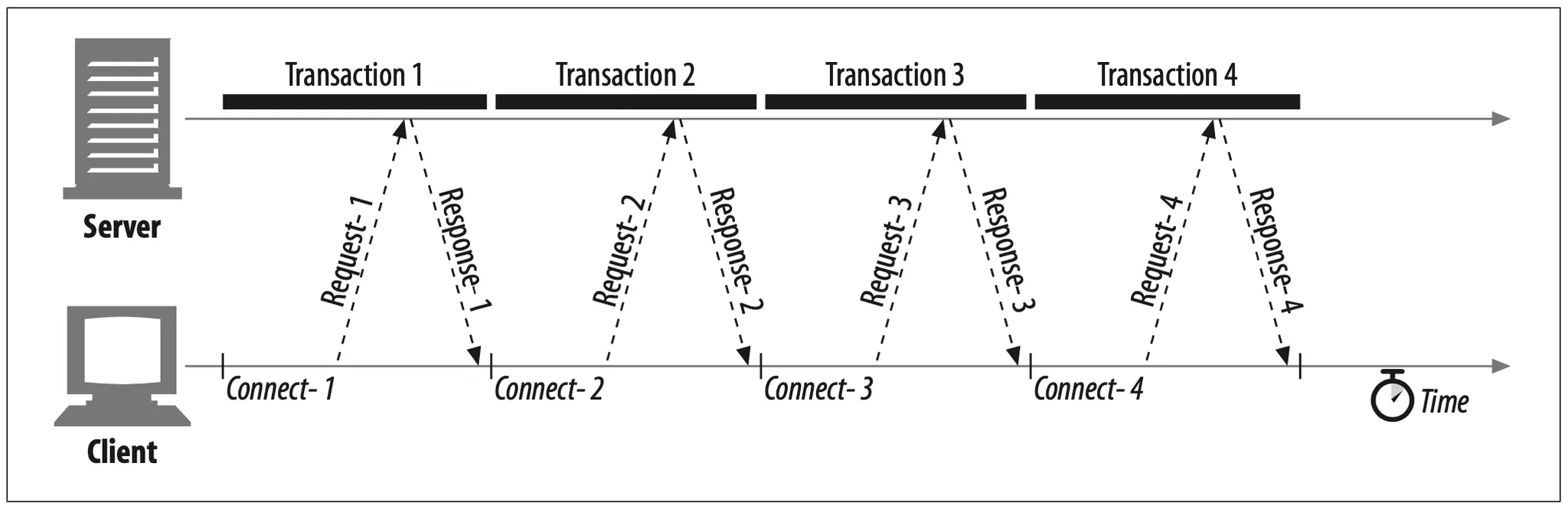

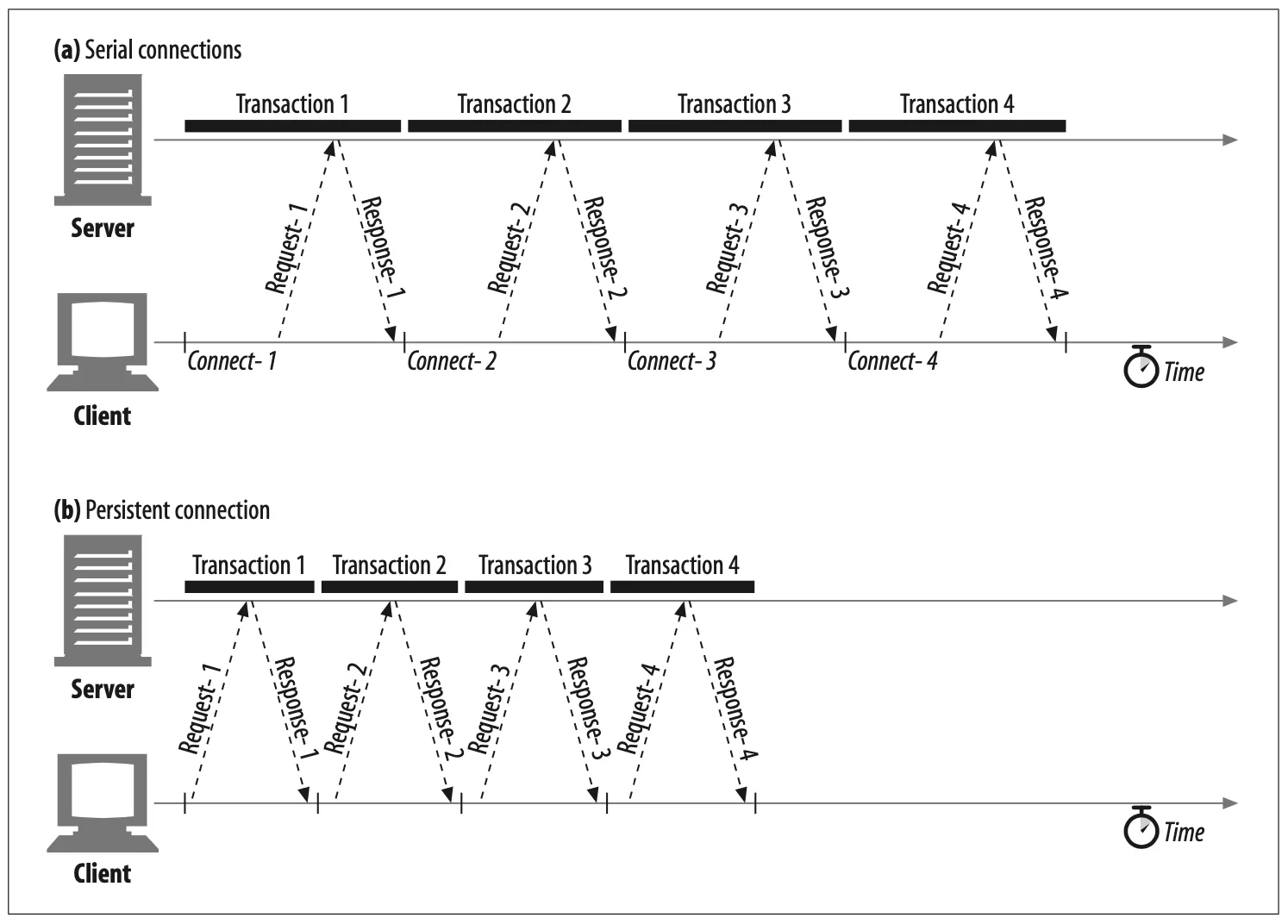

3.2. Serial Transaction Delays

TCP performance delays can add up if the connections are managed naively. For example, suppose you have a web page with three embedded images. Your browser needs to issue four HTTP transactions to display this page: one for the top-level HTML and three for the embedded images. If each transaction requires a new connection, the connection and slow-start delays can add up (see Figure 4-10).

Figure 4-10. Four transactions (serial)

In addition to the real delay imposed by serial loading, there is also a psychological perception of slowness when a single image is loading and nothing is happening on the rest of the page. Users perfer multiple images to load at the same time.

Another disadvantage of serial loading is that some browsers are unable to display anything onscreen until enough objects are loaded, because they don’t know the sizes of the objects until they are loaded, and they may need the size information to decide where to position the objects on the screen. In this situation, the browser may be making good progress loading ojects serially, but the user may be faced with a blank white screen, unaware that any progress is being made at all.

Several current and emerging techniques are available to improve HTTP connection performance. The next several sections discuss four such techniques:

Parallel connections

Concurrent HTTP request across multiple TCP connections

Persistent connections

Reusing TCP connections to eliminate connect/close delays

Pipelined connections

Concurrent HTTP requests across a shared TCP connection

Multiplexed connections

Interleaving chunks of request and responses (experimental)

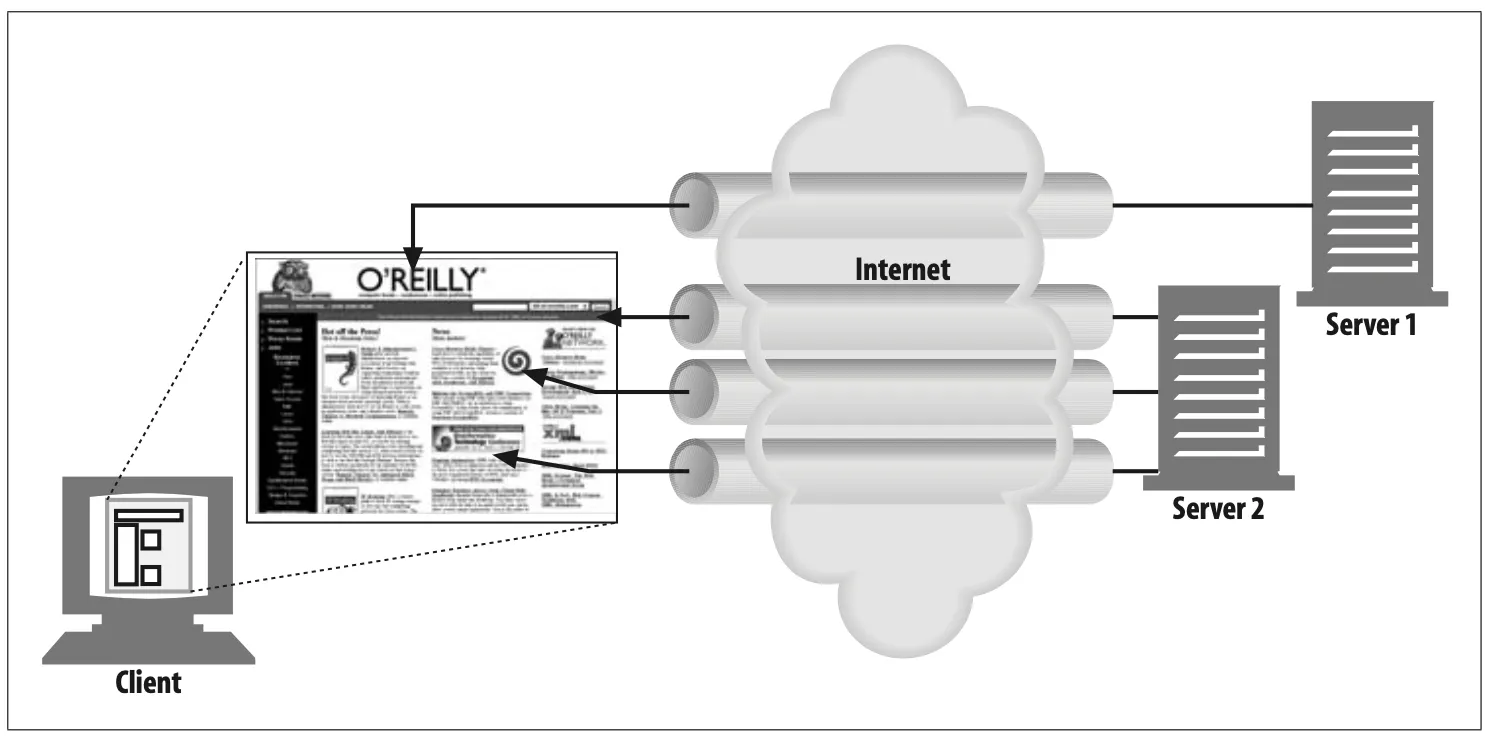

4. Parallel Connections

As we mentioned previously, a browser could naively process each embedded object serially by completely requesting the original HTML page, then the first embedded object, then the second embedded object, etc. But this is too slow!

HTTP allows clients to open multiple connections and perform multiple HTTP transactions in parallel, as sketched in Figure 4-11. In this example, four embedded images are loaded in parallel, with each transaction getting its own TCP connection.

Figure 4-11. Each component of a page involves a sesparate HTTP transaction

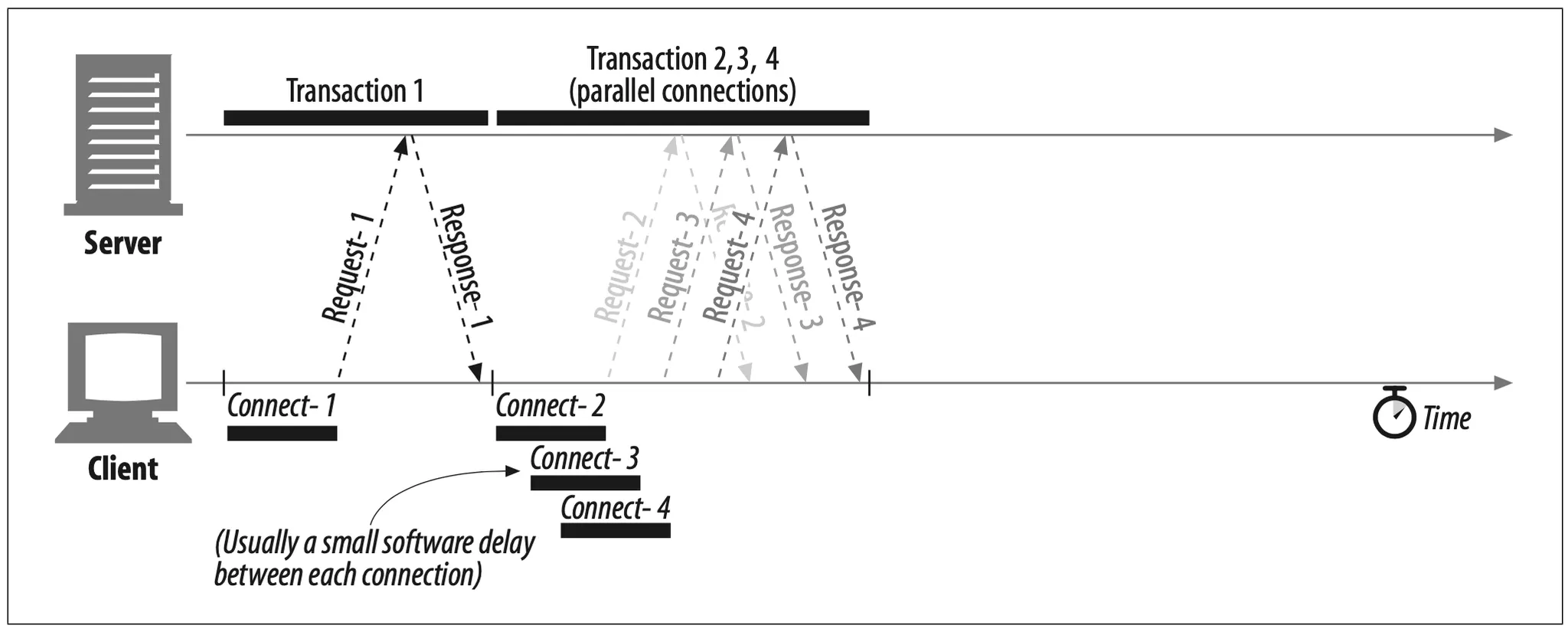

4.1. Parallel Connections May Make Pages Load Faster

Composite pages consisting of embedded objects may load faster if they take advantage of the dead time and bandwidth limits of a single connection. The delays can be overlapped, and if a single connection does not saturate the client's Internet bandwidth, the unused bandwidth can be allocated to loading additional objects.

Figure 4-12 shows a timeline for parallel connections, which is significantly faster than Figure 4-10. The enclosing HTML page is loaded first, and then the remaining three transactions are processed concurrently, each with their own connection. Because the images are loaded in parallel, the connection delays are overlapped.

Figure 4-12. Four transactions (parallel)

4.2. Parallel Connections Are Not Always Faster

Even though parallel connections may be faster, however, they are not always faster. When the client’s network bandwidth is scarce (for example, a browser connected to the Internet through a 28.8-Kbps modem), most of the time might be spent just transferring data. In this situation, a single HTTP transaction to a fast server could easily consume all of the available modem bandwidth. If multiple objects are loaded in parallel, each object will just compete for this limited bandwidth, so each object will load proportionally slower, yielding little or no performance advantage.

Also, a large number of open connections can consume a lot of memory and cause performance problems of their own. Complex web pages may have tens or hundreds of embedded objects. Clients might be able to open hundreds of connections, but few web servers will want to do that, because they often are processing requests for many other users at the same time. A hundred simultaneous users, each opening 100 connections, will put the burden of 10,000 connections on the server. This can cause significant server slowdown. The same situation is true for high-load proxies.

In practice, browsers do use parallel connections, but they limit the total number of parallel connections to a small number (often four). Servers are free to close excessive connections from a particular client.

4.3. Parallel Connections May "Feel" Faster

Okay, so parallel connections don’t always make pages load faster. But even if they don’t actually speed up the page transfer, as we said earlier, parallel connections often make users feel that the page loads faster, because they can see progress being made as multiple component objects appear onscreen in parallel.† Human beings perceive that web pages load faster if there’s lots of action all over the screen, even if a stopwatch actually shows the aggregate page download time to be slower!

5. Persistent Connections

Web clients often open connections to the same site. For example, most of the embedded images in a web page often come from the same web site, and a significant number of hyperlinks to other objects often point to the same site. Thus, an application that initiates an HTTP request to a server likely will make more requests to that server in the near future (to fetch the inline images, for example). This property is called site locality.

For this reason, HTTP/1.1 (and enhanced versions of HTTP/1.0) allows HTTP devices to keep TCP connections open after transactions complete and to reuse the preexisting connections for future HTTP requests. TCP connections that are kept open after transactions complete are called persistent connections. Nonper-sistent connections are closed after each transaction. Persistent connections stay open across transactions, until either the client or the server decides to close them.

By reusing an idle, persistent connection that is already open to the target server, you can avoid the slow connection setup. In addition, the already open connection can avoid the slow-start congestion adaptation phase, allowing faster data transfers.

5.1. Persistent Versus Parallel Connections

As we’ve seen, parallel connections can speed up the transfer of composite pages. But parallel connections have some disadvantages:

•

Each transaction opens/closes a new connection, costing time and bandwidth.

•

Each new connection has reduced performance because of TCP slow start.

•

There is a practical limit on the number of open parallel connections.

Persistent connections offer some advantages over parallel connections. They reduce the delay and overhead of connection establishment, keep the connections in a tuned state, and reduce the potential number of open connections. However, persistent connections need to be managed with care, or you may end up accumulating a large number of idle connections, consuming local resources and resources on remote clients and servers.

Persistent connections can be most effective when used in conjunction with parallel connections. Today, many web applications open a small number of parallel connections, each persistent. There are two types of persistent connections: the older HTTP/1.0+ “keep-alive” connections and the modern HTTP/1.1 “persistent” connections. We’ll look at both flavors in the next few sections.

5.2. HTTP/1.0+ Keep-Alive Connections

Many HTTP/1.0 browsers and servers were extended (starting around 1996) to support an early, experimental type of persistent connections called keep-alive connections. These early persistent connections suffered from some interoperability design problems that were rectified in later revisions of HTTP/1.1, but many clients and servers still use these earlier keep-alive connections.

Some of the performance advantages of keep-alive connections are visible in Figure 4-13, which compares the timeline for four HTTP transactions over serial con- nections against the same transactions over a single persistent connection. The time- line is compressed because the connect and close overheads are removed.

Figure 4-13. Four transactions (serial versus persistent)

5.3. Keep-Alive Operation

Keep-alive is deprecated and no longer documented in the current HTTP/1.1 specification. However, keep-alive handshaking is still in relatively common use by browsers and servers, so HTTP implementors should be prepared to interoperate with it. We’ll take a quick look at keep-alive operation now. Refer to older versions of the HTTP/1.1 specification (such as RFC 2068) for a more complete explanation of keep-alive handshaking.

Clients implementing HTTP/1.0 keep-alive connections can request that a connection be kept open by including the Connection: Keep-Alive request header.

If the server is willing to keep the connection open for the next request, it will respond with the same header in the response (see Figure 4-14). If there is no Con- nection: keep-alive header in the response, the client assumes that the server does not support keep-alive and that the server will close the connection when the response message is sent back.

Figure 4-14. HTTP/1.0 keep-alive transaction header handshake

5.4. Keep-Alive Options

Note that the keep-alive headers are just requests to keep the connection alive. Clients and servers do not need to agree to a keep-alive session if it is requested. They can close idle keep-alive connections at any time and are free to limit the number of transactions processed on a keep-alive connection.

The keep-alive behavior can be tuned by comma-separated options specified in the Keep-Alive general header:

•

The timeout parameter is sent in a Keep-Alive response header. It estimates how long the server is likely to keep the connection alive for. This is not a guarantee.

•

The max parameter is sent in a Keep-Alive response header. It estimates how

many more HTTP transactions the server is likely to keep the connection alive

for. This is not a guarantee.

•

The Keep-Alive header also supports arbitrary unprocessed attributes, primarily for diagnostic and debugging purposes. The syntax is name [= value].

The Keep-Alive header is completely optional but is permitted only when Connec- tion: Keep-Alive also is present. Here’s an example of a Keep-Alive response header indicating that the server intends to keep the connection open for at most five more transactions, or until it has sat idle for two minutes:

Connection: Keep-Alive

Keep-Alive: max=5, timeout=120

5.5. Keep-Alive Restrictions and Rules

Here are some restrictions and clarifications regarding the use of keep-alive connections:

•

Keep-alive does not happen by default in HTTP/1.0. The client must send a

Connection: Keep-Alive request header to activate keep-alive connections.

•

The Connection: Keep-Alive header must be sent with all messages that want to continue the persistence. If the client does not send a Connection: Keep-Alive header, the server will close the connection after that request.

•

Clients can tell if the server will close the connection after the response by

detecting the absence of the Connection: Keep-Alive response header.

•

The connection can be kept open only if the length of the message’s entity body can be determined without sensing a connection close—this means that the entity body must have a correct Content-Length, have a multipart media type, or be encoded with the chunked transfer encoding. Sending the wrong Content-Length back on a keep-alive channel is bad, because the other end of the transaction will not be able to accurately detect the end of one message and the start of another.

•

Proxies and gateways must enforce the rules of the Connection header; the proxy or gateway must remove any header fields named in the Connection header, and the Connection header itself, before forwarding or caching the message.

•

Formally, keep-alive connections should not be established with a proxy server that isn’t guaranteed to support the Connection header, to prevent the problem with dumb proxies described below. This is not always possible in practice.

•

Technically, any Connection header fields (including Connection: Keep-Alive)

received from an HTTP/1.0 device should be ignored, because they may have

been forwarded mistakenly by an older proxy server. In practice, some clients

and servers bend this rule, although they run the risk of hanging on older proxies.

•

Clients must be prepared to retry requests if the connection closes before they receive the entire response, unless the request could have side effects if repeated.

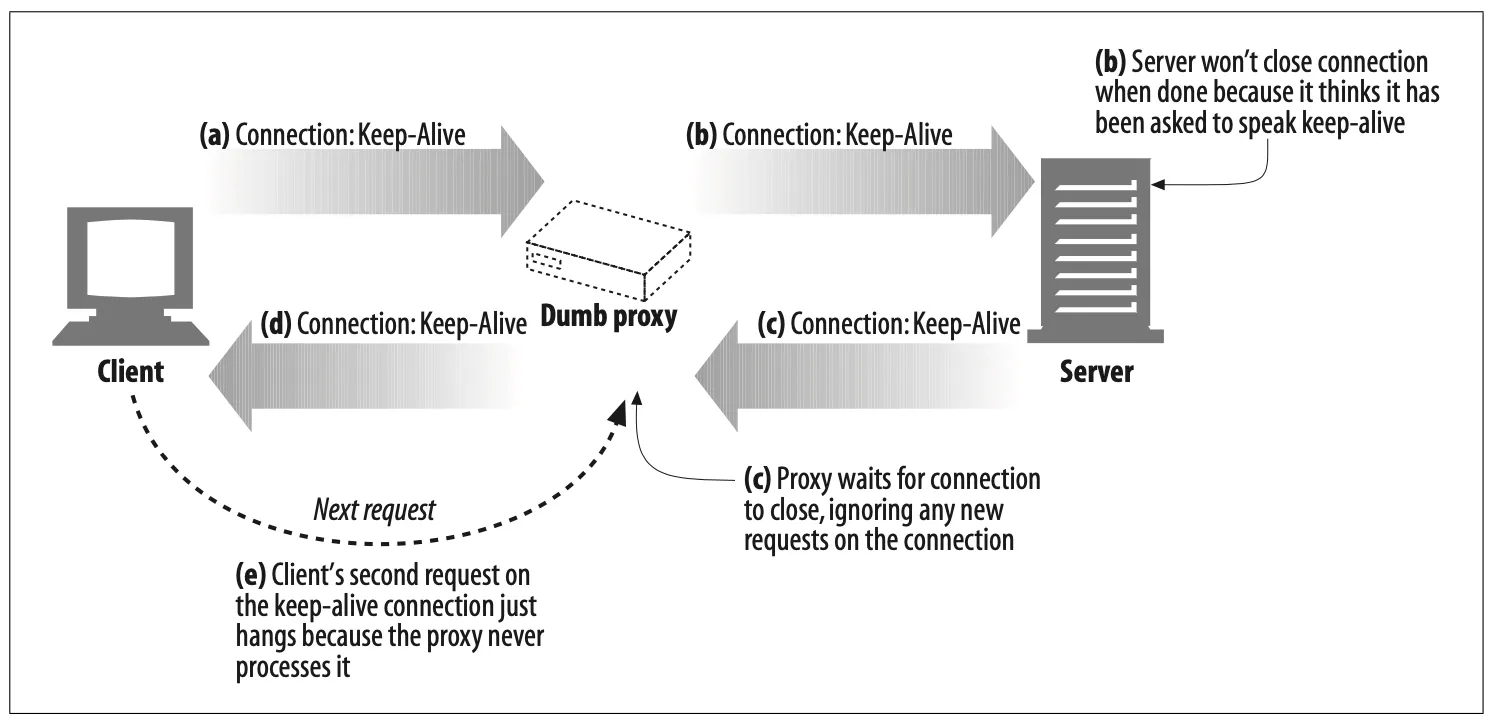

5.6. Keep-Alive and Dumb Proxies

Let’s take a closer look at the subtle problem with keep-alive and dumb proxies. A web client’s Connection: Keep-Alive header is intended to affect just the single TCP link leaving the client. This is why it is named the “connection” header. If the client is talking to a web server, the client sends a Connection: Keep-Alive header to tell the server it wants keep-alive. The server sends a Connection: Keep-Alive header back if it supports keep-alive and doesn’t send it if it doesn’t.

The Connection header and blind relays

The problem comes with proxies—in particular, proxies that don’t understand the Connection header and don’t know that they need to remove the header before proxying it down the chain. Many older or simple proxies act as blind relays, tunneling bytes from one connection to another, without specially processing the Connection header.

Imagine a web client talking to a web server through a dumb proxy that is acting as a blind relay. This situation is depicted in Figure 4-15.

Figure 4-15. Keep-alive doesn't interoperate with proxies that don't support Connection headers

Here’s what’s going on in this figure:

1.

In Figure 4-15a, a web client sends a message to the proxy, including the Connec- tion: Keep-Alive header, requesting a keep-alive connection if possible. The client waits for a response to learn if its request for a keep-alive channel was granted.

2.

The dumb proxy gets the HTTP request, but it doesn’t understand the Connec- tion header (it just treats it as an extension header). The proxy has no idea what keep-alive is, so it passes the message verbatim down the chain to the server (Figure 4-15b). But the Connection header is a hop-by-hop header; it applies to only a single transport link and shouldn’t be passed down the chain. Bad things are about to happen.

3.

In Figure 4-15b, the relayed HTTP request arrives at the web server. When the web server receives the proxied Connection: Keep-Alive header, it mistakenly concludes that the proxy (which looks like any other client to the server) wants to speak keep-alive! That’s fine with the web server—it agrees to speak keep- alive and sends a Connection: Keep-Alive response header back in Figure 4-15c. So, at this point, the web server thinks it is speaking keep-alive with the proxy and will adhere to rules of keep-alive. But the proxy doesn’t know the first thing about keep-alive. Uh-oh.

4.

In Figure 4-15d, the dumb proxy relays the web server’s response message back to the client, passing along the Connection: Keep-Alive header from the web server. The client sees this header and assumes the proxy has agreed to speak keep-alive. So at this point, both the client and server believe they are speaking keep-alive, but the proxy they are talking to doesn’t know anything about keep-alive.

5.

Because the proxy doesn’t know anything about keep-alive, it reflects all the data it receives back to the client and then waits for the origin server to close the connection. But the origin server will not close the connection, because it believes the proxy explicitly asked the server to keep the connection open. So the proxy will hang waiting for the connection to close.

6.

When the client gets the response message back in Figure 4-15d, it moves right along to the next request, sending another request to the proxy on the keep-alive connection (see Figure 4-15e). Because the proxy never expects another request on the same connection, the request is ignored and the browser just spins, making no progress.

7.

This miscommunication causes the browser to hang until the client or server times out the connection and closes it.

Proxies and hop-by-hop headers

To avoid this kind of proxy miscommunication, modern proxies must never proxy the Connection header or any headers whose names appear inside the Connection values. So if a proxy receives a Connection: Keep-Alive header, it shouldn’t proxy either the Connection header or any headers named Keep-Alive.

In addition, there are a few hop-by-hop headers that might not be listed as values of a Connection header, but must not be proxied or served as a cache response either. These include Proxy-Authenticate, Proxy-Connection, Transfer-Encoding, and Upgrade. For more information, refer back to “The Oft-Misunderstood Connection Header.”

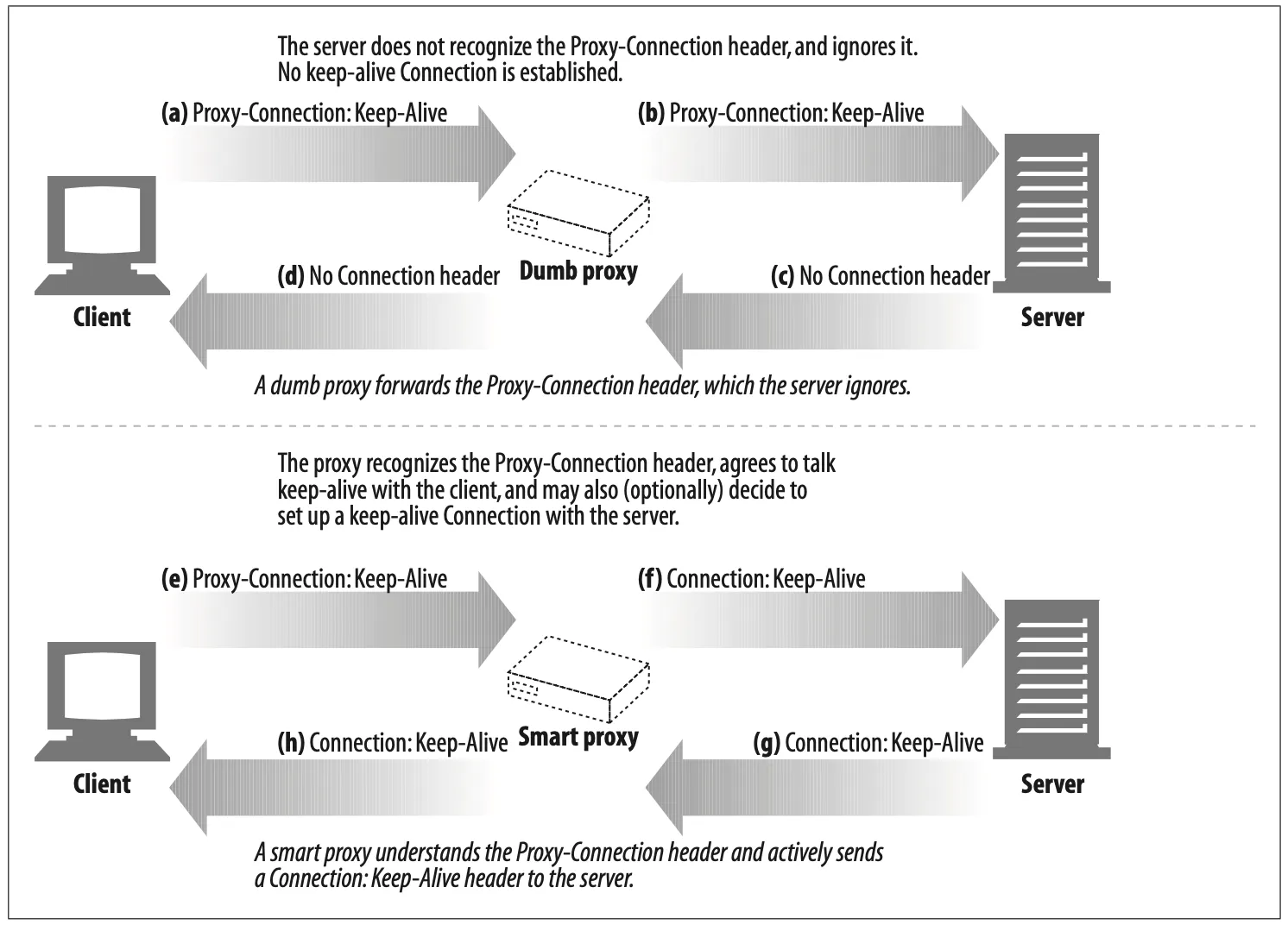

5.7. The Proxy-Connection Hack

Browser and proxy implementors at Netscape proposed a clever workaround to the blind relay problem that didn’t require all web applications to support advanced ver- sions of HTTP. The workaround introduced a new header called Proxy-Connection and solved the problem of a single blind relay interposed directly after the client— but not all other situations. Proxy-Connection is implemented by modern browsers when proxies are explicitly configured and is understood by many proxies.

The idea is that dumb proxies get into trouble because they blindly forward hop-by-hop headers such as Connection: Keep-Alive. Hop-by-hop headers are relevant only for that single, particular connection and must not be forwarded. This causes trou- ble when the forwarded headers are misinterpreted by downstream servers as requests from the proxy itself to control its connection.

In the Netscape workaround, browsers send nonstandard Proxy-Connection exten- sion headers to proxies, instead of officially supported and well-known Connection headers. If the proxy is a blind relay, it relays the nonsense Proxy-Connection header to the web server, which harmlessly ignores the header. But if the proxy is a smart proxy (capable of understanding persistent connection handshaking), it replaces the nonsense Proxy-Connection header with a Connection header, which is then sent to the server, having the desired effect.

Figure 4-16a–d shows how a blind relay harmlessly forwards Proxy-Connection head- ers to the web server, which ignores the header, causing no keep-alive connection to be established between the client and proxy or the proxy and server. The smart proxy in Figure 4-16e–h understands the Proxy-Connection header as a request to speak keep-alive, and it sends out its own Connection: Keep-Alive headers to establish keep-alive connections.

Figure 4-16. Proxy-Connection header fixes single blind relay

This scheme works around situations where there is only one proxy between the client and server. But if there is a smart proxy on either side of the dumb proxy, the problem will rear its ugly head again, as shown in Figure 4-17.

Figure 4-17. Proxy-Connection still fails for deeper hierarchies of proxies

Furthermore, it is becoming quite common for “invisible” proxies to appear in net- works, either as firewalls, intercepting caches, or reverse proxy server accelerators. Because these devices are invisible to the browser, the browser will not send them Proxy-Connection headers. It is critical that transparent web applications implement persistent connections correctly.

5.8. HTTP/1.1 Persistent Connections

HTTP/1.1 phased out support for keep-alive connections, replacing them with an improved design called persistent connections. The goals of persistent connections are the same as those of keep-alive connections, but the mechanisms behave better.

Unlike HTTP/1.0+ keep-alive connections, HTTP/1.1 persistent connections are active by default. HTTP/1.1 assumes all connections are persistent unless otherwise indicated. HTTP/1.1 applications have to explicitly add a Connection: close header to a message to indicate that a connection should close after the transaction is complete. This is a significant difference from previous versions of the HTTP protocol, where keep-alive connections were either optional or completely unsupported.

An HTTP/1.1 client assumes an HTTP/1.1 connection will remain open after a response, unless the response contains a Connection: close header. However, clients and servers still can close idle connections at any time. Not sending Connection: close does not mean that the server promises to keep the connection open forever.

5.9. Persistent Connection Restrictions and Rules

Here are the restrictions and clarifications regarding the use of persistent connections:

•

After sending a Connection: close request header, the client can’t send more requests on that connection.

•

If a client does not want to send another request on the connection, it should send a Connection: close request header in the final request.

•

The connection can be kept persistent only if all messages on the connection have a correct, self-defined message length—i.e., the entity bodies must have correct Content-Lengths or be encoded with the chunked transfer encoding.

•

HTTP/1.1 proxies must manage persistent connections separately with clients and servers—each persistent connection applies to a single transport hop.

•

HTTP/1.1 proxy servers should not establish persistent connections with an HTTP/1.0 client (because of the problems of older proxies forwarding Connec- tion headers) unless they know something about the capabilities of the client. This is, in practice, difficult, and many vendors bend this rule.

•

RegardlessofthevaluesofConnectionheaders,HTTP/1.1devicesmayclosethe connection at any time, though servers should try not to close in the middle of transmitting a message and should always respond to at least one request before closing.

•

HTTP/1.1 applications must be able to recover from asynchronous closes. Cli- ents should retry the requests as long as they don’t have side effects that could accumulate.

•

Clients must be prepared to retry requests if the connection closes before they receive the entire response, unless the request could have side effects if repeated.

•

A single user client should maintain at most two persistent connections to any server or proxy, to prevent the server from being overloaded. Because proxies may need more connections to a server to support concurrent users, a proxy should maintain at most 2N connections to any server or parent proxy, if there are N users trying to access the servers.

6. Pipelined Connections

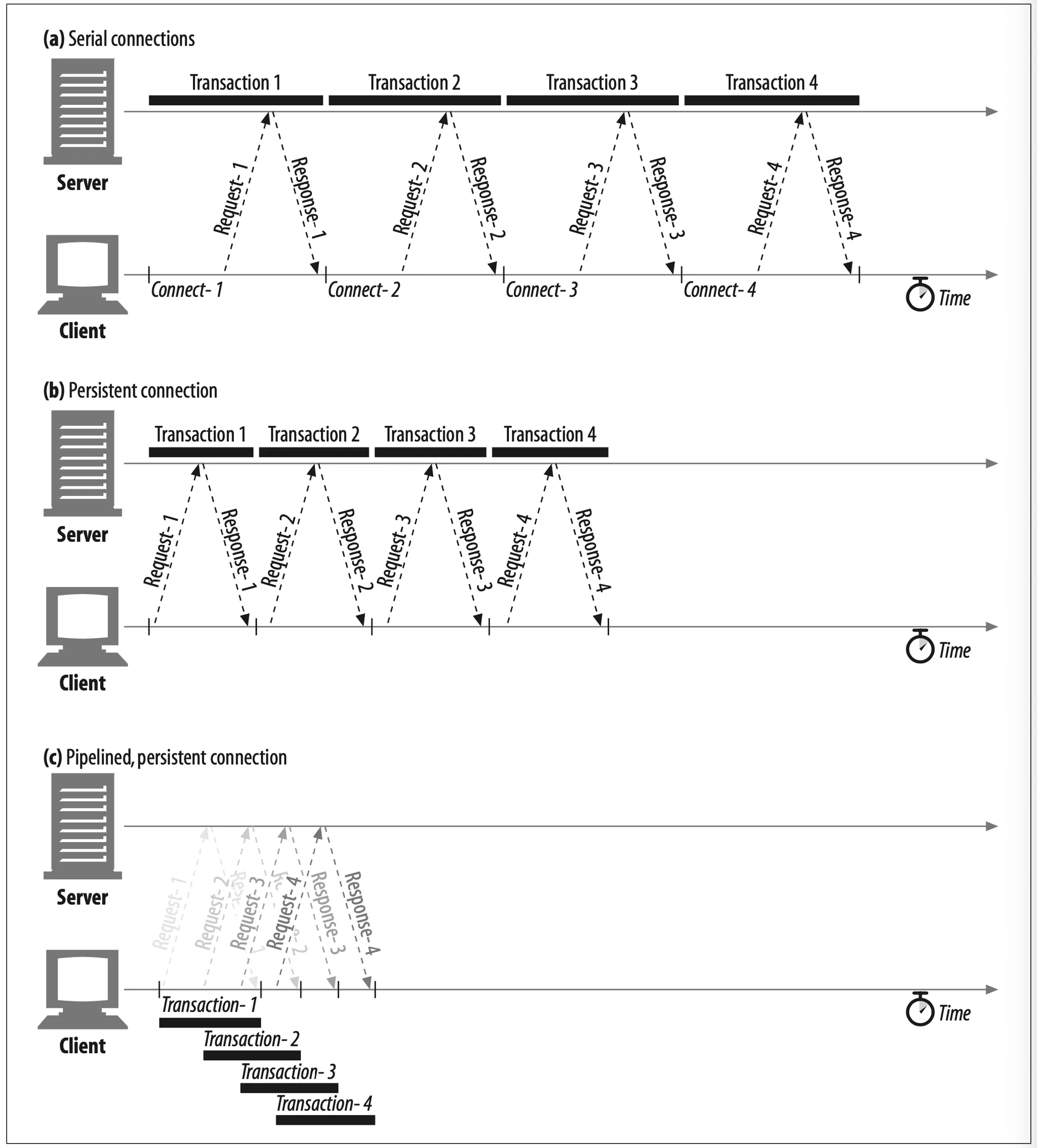

HTTP/1.1 permits optional request pipelining over persistent connections. This is a further performance optimization over keep-alive connections. Multiple requests can be enqueued before the responses arrive. While the first request is streaming across the network to a server on the other side of the globe, the second and third requests can get underway. This can improve performance in high-latency network conditions, by reducing network round trips.

Figure 4-18a-c shows how persistent connections can eliminate TCP connection delays and how pipelined requests (Figure 4-18c) can eliminate transfer latencies.

Figure 4-18. Four transactions (pipelined connections)

There are several restrictions for pipelining:

•

HTTP client should not pipeline until they are sure the connection is persistent.

•

HTTP responses must be returned in the same order as the requests. HTTP messages are not tagged with sequence numbers, so there is no way to match response with request if the response are received out of order.

•

HTTP clients must be prepared for connection to close at time and be prepared to redo any pipelined requests that did not finish. If the client opens a persistent connection and immediately issues 10 requests, the server is free to close the connection after processing only, say, 5 request. The remaining 5 requests will fail, and the client must be willing to handle these premature closes and reissue the requests.

•

HTTP clients should not pipeline request that have side effects (such as POSTs). In genenal, on error, pipelining prevents clients from knowing which of a series of pipelined request were executed by the server. Because nonidempotent requests such as POSTs cannot safely be retried, you run the risk of some methods never being executed in error conditions.

7. The Mysteries of Connection Close

Connection management—particularly knowing when and how to close connec- tions—is one of the practical black arts of HTTP. This issue is more subtle than many developers first realize, and little has been written on the subject.

7.1. "At will" Disconnection

Any HTTP client, server, or proxy can close a TCP transport connection at any time. The connections normally are closed at the end of a message,* but during error con- ditions, the connection may be closed in the middle of a header line or in other strange places.

This situation is common with pipelined persistent connections. HTTP applications are free to close persistent connections after any period of time. For example, after a persistent connection has been idle for a while, a server may decide to shut it down.

However, the server can never know for sure that the client on the other end of the line wasn’t about to send data at the same time that the “idle” connection was being shut down by the server. If this happens, the client sees a connection error in the middle of writing its request message.

7.2. Content-Length and Truncation

Each HTTP response should have an accurate Content-Length header to describe the size of the response body. Some older HTTP servers omit the Content-Length header or include an erroneous length, depending on a server connection close to signify the actual end of data.

When a client or proxy receives an HTTP response terminating in connection close, and the actual transferred entity length doesn’t match the Content-Length (or there is no Content-Length), the receiver should question the correctness of the length.

If the receiver is a caching proxy, the receiver should not cache the response (to mini- mize future compounding of a potential error). The proxy should forward the ques- tionable message intact, without attempting to “correct” the Content-Length, to maintain semantic transparency.

7.3. Connection Close Tolerance, Retries, and Idempotency

Connections can close at any time, even in non-error conditions. HTTP applica- tions have to be ready to properly handle unexpected closes. If a transport connec- tion closes while the client is performing a transaction, the client should reopen the connection and retry one time, unless the transaction has side effects. The situation is worse for pipelined connections. The client can enqueue a large number of requests, but the origin server can close the connection, leaving numerous requests unprocessed and in need of rescheduling.

Side effects are important. When a connection closes after some request data was sent but before the response is returned, the client cannot be 100% sure how much of the transaction actually was invoked by the server. Some transactions, such as GETting a static HTML page, can be repeated again and again without changing anything. Other transactions, such as POSTing an order to an online book store, shouldn’t be repeated, or you may risk multiple orders.

A transaction is idempotent if it yields the same result regardless of whether it is exe- cuted once or many times. Implementors can assume the GET, HEAD, PUT, DELETE, TRACE, and OPTIONS methods share this property.* Clients shouldn’t pipeline nonidempotent requests (such as POSTs). Otherwise, a premature termina- tion of the transport connection could lead to indeterminate results. If you want to send a nonidempotent request, you should wait for the response status for the previ- ous request.

Nonidempotent methods or sequences must not be retried automatically, although user agents may offer a human operator the choice of retrying the request. For exam- ple, most browsers will offer a dialog box when reloading a cached POST response, asking if you want to post the transaction again.

7.4. Graceful Connection Close

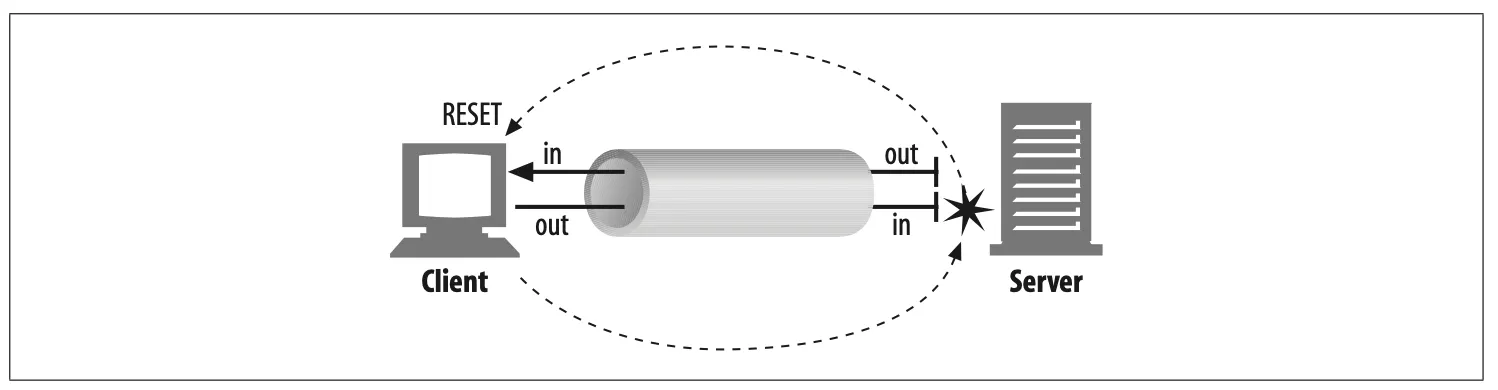

TCP connections are bidirectional, as shown in Figure 4-19. Each side of a TCP con- nection has an input queue and an output queue, for data being read or written. Data placed in the output of one side will eventually show up on the input of the other side.

Figure 4-19. TCP connections are bidirectional

Full and half closes

An application can close either or both of the TCP input and output channels. A close( ) sockets call closes both the input and output channels of a TCP connection. This is called a “full close” and is depicted in Figure 4-20a. You can use the shutdown( ) sockets call to close either the input or output channel individually. This is called a “half close” and is depicted in Figure 4-20b.

Figure 4-20. Full and half close

TCP close and reset errors

Simple HTTP applications can use only full closes. But when applications start talk- ing to many other types of HTTP clients, servers, and proxies, and when they start using pipelined persistent connections, it becomes important for them to use half closes to prevent peers from getting unexpected write errors.

In general, closing the output channel of your connection is always safe. The peer on the other side of the connection will be notified that you closed the connection by getting an end-of-stream notification once all the data has been read from its buffer.

Closing the input channel of your connection is riskier, unless you know the other side doesn’t plan to send any more data. If the other side sends data to your closed input channel, the operating system will issue a TCP “connection reset by peer” mes- sage back to the other side’s machine, as shown in Figure 4-21. Most operating sys- tems treat this as a serious error and erase any buffered data the other side has not read yet. This is very bad for pipelined connections.

Figure 4-21. Data arriving at closed connection generates "connection reset by peer" error

Say you have sent 10 pipelined requests on a persistent connection, and the responses already have arrived and are sitting in your operating system’s buffer (but the application hasn’t read them yet). Now say you send request #11, but the server decides you’ve used this connection long enough, and closes it. Your request #11 will arrive at a closed connection and will reflect a reset back to you. This reset will erase your input buffers.

Graceful close

The HTTP specification counsels that when clients or servers want to close a connec- tion unexpectedly, they should “issue a graceful close on the transport connection,” but it doesn’t describe how to do that.

In general, applications implementing graceful closes will first close their output channels and then wait for the peer on the other side of the connection to close its output channels. When both sides are done telling each other they won’t be sending any more data (i.e., closing output channels), the connection can be closed fully, with no risk of reset.

Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that the peer implements or checks for half closes. For this reason, applications wanting to close gracefully should half close their output channels and periodically check the status of their input channels (look- ing for data or for the end of the stream). If the input channel isn’t closed by the peer within some timeout period, the application may force connection close to save resources.